-

Titolo

-

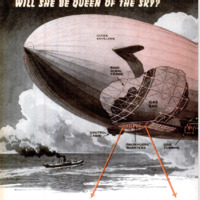

Will she be queen of the sky?

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Will she be queen of the sky?

-

extracted text

-

WHEN the giant airship Hindenburg

exploded into flames at Lakehurst,

N. J., on the evening of May 6, 1937, many

people believed that it was the end of a |

noble experiment in lighter-than-air travel. |

It was, indeed, the end of an era in that

field. But a new era began soon after

Hitler's armies invaded Poland less than

two and a half years later. American air-

ships, nonrigid blimps, were drafted into

patrol duty along our coasts. Little was

said then about what those airships were

doing, and only a littie

more may be said to-

day about what they

have done. But it is

known that literally

hundreds of them have

piled up a log of hun-

dreds of thousands of

hours of strenuous

patrol and convoy

duty with a phenome-

nally low casualty

record.

On the basis of this

record, backed by an impressive mass of

figures and facts, American airship men are

now prepared to bid for a place in the

world’s postwar commercial aviation pro-

gram.

Anyone who looks at the over-all picture

of this air program will have trouble shrug-

ging off the airship. Its advocates offer—

and back with facts—many reasons for its

revival in world commerce. Chief among

the reasons are the airship’s speed and

safety, its economy of operation, its reli-

ability, and its load capacity. And Ameri-

cans can add this clincher: we have a

virtual world monopoly on helium, safest

known gas for inflating lighter-than-air

craft and clearly the key to successful

operation of airships.

It was the Germans who developed the

airship and proved its commercial worth.

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin did his major

work of development before and during

World War I. Zeppelin, incidentally, made

his first flight here in America in 1863, in a

captive observation balloon of the Union

Army. He had come here as a military ob-

server, remained to fight for a time, and

returned to Germany before the Civil War

had ended.

During the years of trial and develop-

ment, nearly half a million passengers were

carried by airships without a single passen-

ger fatality until the Hindenburg fire. The

really significant figures come from the

records of the Graf Zeppelin and the Hinden-

burg, both built. specially for transoceanic

passenger and freight trade.

The Graf Zeppelin

made 590 commercial

flights totaling 17,177

hours and 1,053,618

miles. She made 144

ocean crossings and

carried more than 13,-

000 passengers and

250,000 pounds of mail

and freight. Her log

shows a flight to the

Arctic and one to

Egypt, and she circled

the globe. She was re-

tired without ever having had a serious

accident. | |

The Hindenburg, larger and more modern

than the Graf Zeppelin, was in service less |

than a year. But in that time she made 63

flights, 37 ocean crossings, was in the air |

3,088 hours, flew 209,527 miles, and carried |

more than 3,000 passengers and 41,000 |

pounds of mail and freight. |

American blimps also have a peacetime |

record well worth noting. Until they were |

taken over by the Navy, Goodyear’'s com- |

mercial blimps had made 152,441 flights |

totaling 93,096 hours and 4,166,390 miles. |

They had carried 407,171 passengers with- |

out so much as a minor injury to anyone. |

Military airships—that is, those rigid- |

framed dirigibles with which we and other

nations experimented for 15 years after |

1920—have had no such record of success. |

Five of those huge ships met destruction in |

tragic fashion, and the world still remem- |

bers them. Each of those disastrous acci-

dents, however, had its reason. |

In August 1921, the British ZR-2 broke in |

two and burned, causing a loss of 62 lives. |

‘The ZR-2 was a hydrogen-filled ship copied |

from a lightly built German “zep” captured

at the end of World War I; it was flown by

a crew unfamiliar with air stresses.

In December 1923, the French Dizmude

vanished over the Mediterranean with a

crew of 53 men. The Dizmude was a light-

weight, hydrogen-inflated German ship

seized after the armistice, and the French

crew was inexperienced.

In September 1925, the U. S. Navy's Shen-

andoah broke in two in a line squall near

Ava, Ohio, and 14 of her crew were lost.

The Shenandoah was a modified copy of a |

German ‘“zep” built in 1916, a touchy light-

weight in which it was suicidal to enter

any violent storm area.

In April 1933, the U.S. Navy's Akron

crashed into the sea off the New Jersey, coast

with a loss of 73 lives. She ran blindly into

a violent thunderstorm and, because of a

faulty altimeter, slammed her tail into the

waves while trying to maneuver out of the

storm.

In February 1935, the U. S. Navy's Macon

was forced down off the Pacific coast

and was lost. Two men died with her. She,

too, was fundamentally a sound ship. But

she was ordered to put out on fleet maneu-

vers before changes ordered in her aft struc-

ture had been completed, and she lost a fin

in a bit of rough weather. Subsequently, she

lost a good deal of gas and settled on the

ocean, where the waves ripped her to pieces.

Of these five military airships, only the

Akron and the Macon were even compara-

tively modern. Airmen who know what

happened insist that neither ship should

have been lost. Any sensible flyer goes

around a storm, not into it, and with today’s

aerology he knows when he is approaching

a storm area and how to avoid it. Both the

Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg met and

mastered such situations repeatedly. In

fact, the fate of these military airships

merely emphasizes the safety record of the

Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenbury.

In considering air travel, we naturally

think of speed. And in thinking of speed

over long distances, most of us turn in-

stinctively to the 350-miles-an-hour air-

plane. But over long distances, factors other

than maximum speed under ideal conditions

must be considered. There are layovers,

turn backs, delays, overnight stops. The

longer the trip, the more these factors

affect elapsed-time speed.

Rear Admiral Charles E. Rosendahl, prob-

ably America's most experienced airship

man, has compiled eye-opening figures on

comparative air speeds. He points out that

over a five-year period ending late in 1941

transpacific commercial planes on schedule

between San Francisco and Hong Kong

showed elapsed-time averages of about 35

miles an hour westward and 33 miles an

hour eastward. Bad-weather delays, circui-

tous routes, and overnight stops greatly

reduced actual flying time and increased

elapsed time.

Admiral Rosendahl's figures also show

that commercial air travelers bound across

the North Atlantic just before the present

war were taken in the winter months by a

roundabout southern route requiring an

average of four days and 16 hours per

passage. This, according to Admiral Rosen-

dahl's calculations, gave them an average

clapsed-time speed of only about 30 miles

an hour.

‘The only comparable airship figures are

those of the Graf Zeppelin and the Hinden-

burg. In 1928 the Graf Zeppelin made the

trip from Japan to San Francisco in 69

hours, at an average speed of nearly 75

miles an hour, elapsed time. The Hinden-

burg's average operational speed, also

elapsed time, was nearly 65 miles an hour

for all her ocean passages. The passenger-

plane schedule from San Francisco to Hong

Kong wes six days and seven hours. An

airship with the Hindenbury's average per-

formance would make the same trip in

about four and a half days.

The airships advantage here comes from

the fact that it does not have to make

Stops for refueling, that it can halt in mid-

air for motor repairs, that it has sufficient

range to go far around a bad-weather area

and can even seek a clear area and cruise

‘with only enough movement for steerageway

until bad weather ahead clears up. In fact,

the Hindenbury’s record shows that she

never falled to make a scheduled com-

mercial trip; she took of several times

|when the weather was so bad that all

airplanes were grounded; and she never

was more than 12 hours late on a scheduled

North Atlantic westward crossing or six

hours late on an eastward crossing. Also,

its ability to hover permits an airship to de.

lay its landing if that is necessary. Oncs,

warned by radio of a revolution, a German

airship postponed her landing at Recife,

Brazil, and merely headed into the wind for

two days.

+ For hauls of 1,000.to 2,000. miles the air-

ship cannot compete with the airplane in

speed, though it can offer stiff competition

in economy of operation. Passenger revenue

alone covered more than 75 percent of all

costs of operating the Hindenburg, including

amortization, and the ship never carried &

capacity load of paying passengers.

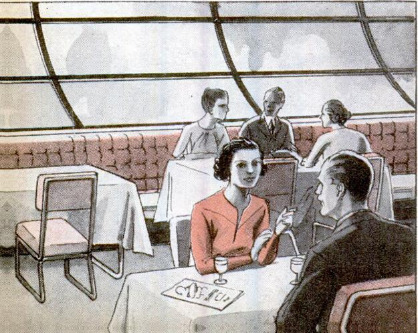

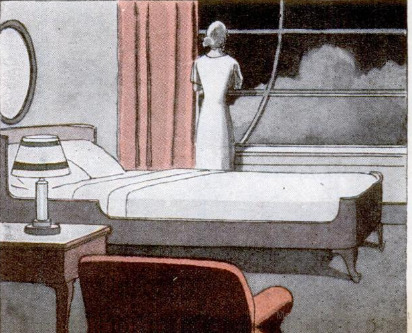

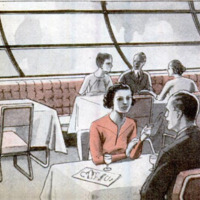

Passenger comfort is another notable

factor. The Hindenburg had 25 two-berth

staterooms, smoking and writing rooms,

promenades, three bars, and deck space

totaling an’ efghth of an acre. Her noise

level was rated at 61 decibels, lower even

than that of a Pullman car. There was not

enough vibration to ripple the surface of a

glasstul of water. And because of its size,

the airship absorbs the air bumps which

toss an airplane around to the discomfort of

its passengers. According to the records,

there never was a case of airsickness or

seasickness on elther the Graf Zeppelin or

the Hindenburg.

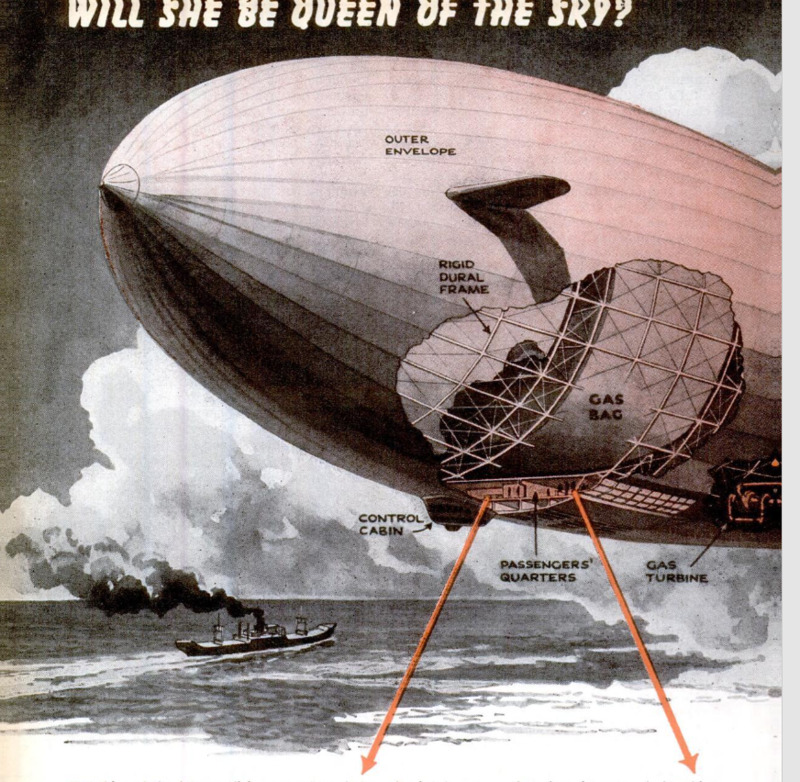

Can we build good airships? We built

two, the Akron and the Macon, both of

which were lost, according to findings of

official courts of Inquiry, because of opera-

tonal mistakes. Goodyear now han in blue-

print plans for a ship of 10,000,000 cubic

feet capacity, half again as largo as the

Macon and more than a third larger than

the Hindenburg. Tested designs are definite

Improvements on the best that the Germans

ever made. New materials made available

since the war began will permit still further

Improvement.

Professor J. C. Hunsaker of the Massa-

chusetts Instituto of Technology, a noted

‘aeronautical scientist, sees the transatlantic

services of the future falling into three cate-

goriea: a five-day steamship service, a one-

day airplane service, and a two-day airship

schedule.

“Consideration of the operating record of

the Hindenburg in North Atlantic service,”

he says, “leads to the conclusion that a sim-

flar airship of 28 percent greater displace-

ment should have a payload of 100 passen-

gers and 20,000 pounds of mail and express

When inflated with helium.”

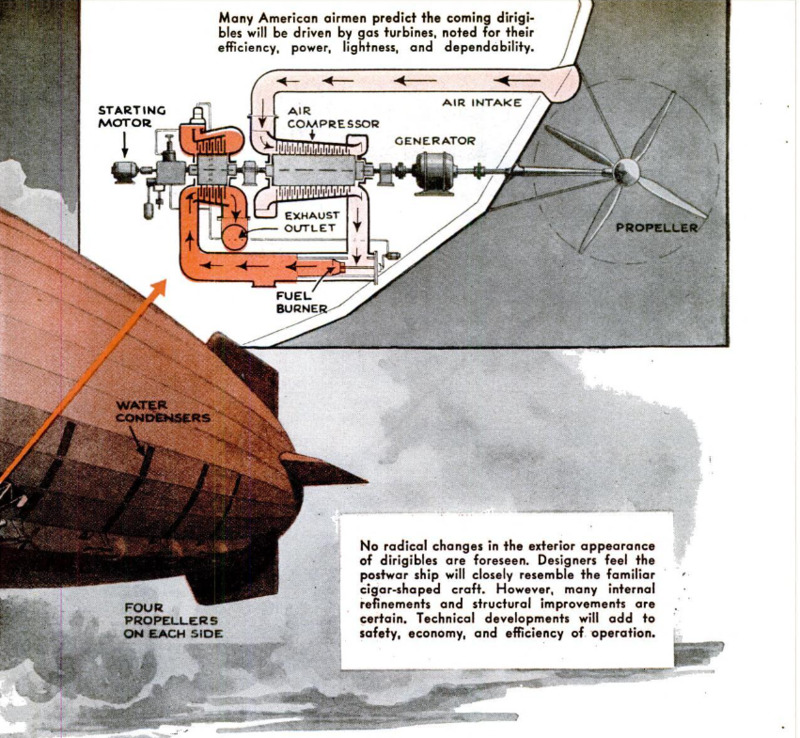

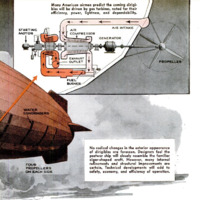

American designers were the first to move

the engines inboard to reduce drag, and to

swivel the propellers for better control. Now

it is suggested that both engines and pro-

pellers be placed in a central tunnel running

the length of the ship, which would further

reduce drag and improve control, and at the

same time add a jet-propulsion effect. Also,

it seems likely that tomorrow's airships will

De using gas turbines for power, thus great-

ly increasing efficiency. These changes, ex-

perienced lighter-than-air authorities be-

lieve, could increase airship cruising speeds

to as much as 125 miles an hour.

As for costs, it is worth noting that our

whole military airship program up to 1941

cost less, for instance, than LaGuardia Field,

New York City’s airport. This included the

building of three rigid airships—the Shen-

andoah, the Akron, and the Macon—con-

struction of two airship docks and bases,

one on each coast, and five mooring masts,

one on a ship for sea moorings. This air-

ship program cost $30,000,000. LaGuardia

Field cost $42,000,000.

Finally, America’s monopoly on helium

makes an American airship program a

“natural.” Add to that the fact that its ship-

ment and storage are both complicated and

expensive, which means it probably will re-

main here. Helium has nearly 93 percent

as much lift as hydrogen, is an inert gas,

and is foolproof and virtually accident-

proof. Given capable handling, the weather

information now available, and intelligent

operation, American-built helium-filled air-

ships would seem to demand a place in any

international program of postwar com-

mercial aviation.

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1945-05

-

pagine

-

129-135

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)