Il dilemma della trincea

La Prima guerra mondiale, come ogni altro conflitto, fu definita da fattori sia tecnologici che culturali. L’artiglieria e il fuoco automatico sono, senza dubbio, i due elementi tecnologici fondamentali per comprendere la guerra di logoramento, l’esperienza delle trincee e le conseguenze che queste ebbero sulla storia e sulla cultura europee.

In poche parole, la loro azione combinata rese la difesa molto più semplice dell’attacco. I soldati furono costretti a cercare riparo nel terreno e iniziò così la guerra di trincea, un fenomeno nuovo nella storia dell’umanità. Artiglieria e mitragliatrici plasmarono letteralmente il paesaggio di guerra, trasformando lo spazio tra le trincee contrapposte in una “terra di nessuno”, priva di vita, disseminata di cadaveri e crivellata di crateri.

L’efficienza distruttiva dell’artiglieria e delle armi automatiche fu amplificata da dottrine militari incapaci di tenere conto dell’innovazione tecnologica. I massacri che associamo alla Prima guerra mondiale – uomini lanciati in una corsa disperata contro le raffiche delle mitragliatrici – sono una diretta conseguenza di questo divario tra tecnologia e cultura.

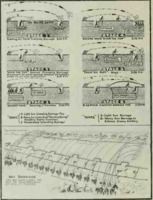

La teoria della guerra di trincea era semplice: un bombardamento d’artiglieria avrebbe dovuto neutralizzare i nidi di mitragliatrici nemici e i reticolati di filo spinato che li proteggevano. Successivamente, i soldati avrebbero dovuto attraversare la terra di nessuno, protetti dal “tiro di sbarramento” (colpi d’artiglieria coordinati con l’avanzata delle truppe). L’obiettivo finale era conquistare le trincee nemiche e, più in generale, aprire una breccia che consentisse di attraversare la linea del fronte e invadere il territorio avversario. Lo scopo rimase, per tutta la durata della guerra, quello di tornare a una guerra di movimento.

Nella stragrande maggioranza dei casi, la realtà fu ben diversa. L’artiglieria non era efficace nel distruggere le postazioni nemiche, ma funzionava benissimo nell’avvertire il nemico dell’imminente attacco. I soldati, una volta allo scoperto, si trovavano a correre contro mitragliatrici ancora intatte. Problemi di comunicazione rendevano il tiro di sbarramento spesso impreciso e talvolta letale per gli stessi attaccanti. I soldati che riuscivano a raggiungere le trincee nemiche trovavano spesso il filo spinato ancora intatto, magari attorcigliato ma non neutralizzato dalle granate. I difensori, che durante il bombardamento si erano rifugiati nelle trincee arretrate, tornavano alle loro postazioni e, il più delle volte, respingevano l’attacco.

Questo, in poche parole, era il dilemma tecno-culturale della guerra di trincea. Molte delle innovazioni (reali o immaginate) presentate in questa esposizione sono tentativi di risolverlo. Ma un deus ex machina non arrivò mai. La guerra finì per l’esaurimento delle risorse morali e materiali delle Potenze Centrali, non grazie al maggiore ingegno o eroismo di uno dei due schieramenti.

Tecnologia contro cultura

Nell’agosto del 1914, l’ultimo conflitto combattuto in territorio europeo era stata la guerra franco-prussiana. Tra il 1870 e il 1871 la Prussia sconfisse la Francia grazie a un attacco fulmineo che portò la battaglia ben all’interno del territorio nazionale francese.

Le conseguenze di questa vittoria per la storia europea furono enormi: a Versailles nacque uno Stato tedesco unificato. L’umiliazione subita dai francesi fu un elemento fondamentale della rivalità tra Francia e Germania che avrebbe innescato l’inizio della Prima guerra mondiale. Ma le conseguenze culturali furono altrettanto profonde. La vittoria prussiana rafforzò l’idea che un attacco rapido e travolgente fosse la chiave per la vittoria in ogni guerra. In tutti gli eserciti, dottrine e manuali militari insegnavano che l’attacco frontale era l’unico modo per sconfiggere il nemico e dimostrare la superiorità nazionale.

Questa visione era riassunta dall’espressione “élan vital” (slancio vitale o forza vitale), presa in prestito dal filosofo Henri Bergson e applicata in modo improprio ai corpi nazionali. I popoli che avessero dimostrato un più forte élan vital avrebbero vinto una competizione darwiniana tra nazioni. E l’unico modo per dimostrare il proprio slancio vitale sul campo di battaglia era attaccare fino all’ultimo, con cariche di cavalleria o all’arma bianca. Nel 1913, il Ministero della Guerra francese predicava che “Solo l’offensiva può spezzare la volontà dell’avversario e […] la difesa non conduce mai alla vittoria”. Nonostante avesse avuto un anno intero per osservare i massacri sul fronte occidentale, nel 1915 Luigi Cadorna, Comandante Supremo italiano, scriveva che esistevano solo due modi per ottenere la vittoria: “La superiorità di fuoco e l’irresistibile movimento in avanti. Il secondo è più importante (vincere significa andare avanti)”.

Purtroppo, questa fantasia, che vedeva la guerra come una lotta di volontà piuttosto che come uno scontro di mezzi e risorse, si scontrava con una realtà tecnica che rendeva la difesa più facile ed economica dell’attacco. Il fuoco automatico permetteva a pochi uomini in postazioni fisse di falciare centinaia di nemici all’assalto. Il tiro d’artiglieria poteva devastare le compatte formazioni degli assalitori. La cavalleria, epitome della guerra eroica e dinamica, fu presto resa obsoleta e gradualmente sostituita da aerei e carri armati.

Tuttavia, le dottrine militari cambiarono con sorprendente lentezza. Nonostante alcune innovazioni (la difesa elastica e le tattiche di infiltrazione), la carica frontale rimase la norma per tutta la durata del conflitto.

Esplora la realtà della guerra nel nostro database

-

Guastatori italianiOltre ai reticolati tesi tra tronco e tronco, v'erano delle reti metalliche disposte in ogni verso. In queste immense ragnatele di acciaio i nostri plotoni esploratori andavano avanti, passo passo, tagliando i fili, aprendo un varco dopo l'altro. Erano plotoni corazzati, col casco pesante fatto a cuffia, gorgiera, le spalliere, coperti di armatura come guerrieri medioevali, muniti di scudo. Erano i fantastici pionieri della battaglia.

Guastatori italianiOltre ai reticolati tesi tra tronco e tronco, v'erano delle reti metalliche disposte in ogni verso. In queste immense ragnatele di acciaio i nostri plotoni esploratori andavano avanti, passo passo, tagliando i fili, aprendo un varco dopo l'altro. Erano plotoni corazzati, col casco pesante fatto a cuffia, gorgiera, le spalliere, coperti di armatura come guerrieri medioevali, muniti di scudo. Erano i fantastici pionieri della battaglia. -

A One-Man "Tank" for the Barbed-Wire CutterA One-Man "Tank" for the Barbed-Wire Cutter

A One-Man "Tank" for the Barbed-Wire CutterA One-Man "Tank" for the Barbed-Wire Cutter -

The Failure of the New German TacticLa Faillite de la Nouvelle Tactique Allemande

The Failure of the New German TacticLa Faillite de la Nouvelle Tactique Allemande -

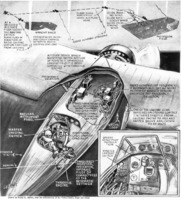

Automatic Landing for AirplanesAutomatic Landing For Airplanes

Automatic Landing for AirplanesAutomatic Landing For Airplanes -

Paris Prepares for GasParis Prepares for Gas. Gas Masks for Civilians . . . Gas-Proof Shelters and Cellars . . . Emergency Squads Equipped With Gas-Proof Clothing and Steel Helmets

Paris Prepares for GasParis Prepares for Gas. Gas Masks for Civilians . . . Gas-Proof Shelters and Cellars . . . Emergency Squads Equipped With Gas-Proof Clothing and Steel Helmets -

L'avion en libelluleL'avion en libellule

L'avion en libelluleL'avion en libellule -

Le duel du chasseur et du bombardierLe duel du chasseur et du bombardier

Le duel du chasseur et du bombardierLe duel du chasseur et du bombardier -

Que vaut la flotte des soviéts?Que vaut la flotte des soviéts?

Que vaut la flotte des soviéts?Que vaut la flotte des soviéts?