-

Titolo

-

Pigeon Messengers of Peace and War

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Pigeon Messengers of Peace and War

-

extracted text

-

DESPITE the advances made in scientific methods of communications, homing pigeons, message bearers of the early Egyptians, are still relied on to maintain contact between widely separated places when all other means have failed. Whether the ability of these racing- birds to return to their home lofts when released at distant points is due to instinct, intelligence or to some yet unknown power of sense direction has not been definitely established.

Many reasons have been offered, and it has even been suggested that a network of delicate electric forces might be responsible for the pigeons' faculty of finding their ways back home after being carried in masked cages to places hundreds of miles away.

Numbers of these birds are credited with achieving tremendous tasks and heroic services.

A short time ago, a fishing party left a Panama port in a stanch vessel, but were not heard from for several days during which a terrific storm raged over that locality. Preparations were being made to institute search for the boat or evidence of its fate, when a homing pigeon that had been taken by one of the crew of the "lost" ship, appeared at the government station, dripping wet and nearly exhausted. It bore a message to the effect that all was well aboard the fishing vessel and gave the location of the craft.

While it is common for homing pigeons to cover courses of 200 or 300 miles, some can fly more than 1,000 miles without apparent harm. Such flights are generally made in a series of "hops," the birds taking to shelter at night and resuming their journeys with daylight. Heavy rainstorms have little effect on them, and many records of fast flying have been made by pigeons forced to go through steady downpours. Nature protects them, covering the wings with a natural powderlike substance which keeps the moisture from penetrating the skin.

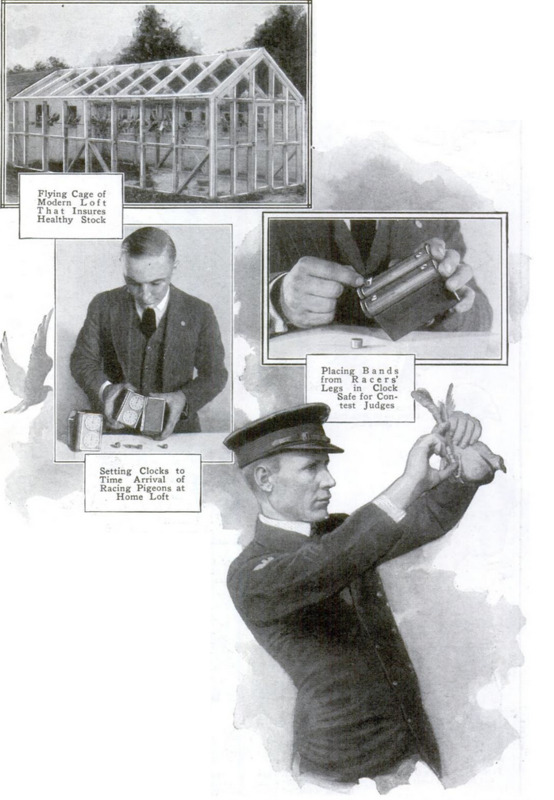

In order to teach the “squeaker” as the youngster is called, a trainer first drills it to "trap" properly. This consists in entering the loft through a swinging-gate arrangement which hangs on a pivoted shaft. Alighting on the landing board, the bird is coaxed by feed within to thrust itself against wire strands which rise upward as it passes and drop into place again to prevent the pigeon's exit. Backward birds are urged by the gentle use of a light whip. After they have learned to trap, they are taken from one to two miles from home and "tossed," or released, to fly back. The distance is gradually increased, the trainer purposely keeping the little students hungry to assure their return for food, since a carefully raised homer is not likely to forage for food, especially on short flights. As they progress, courses of 500 or 600 miles become a regular feat for the pigeons. While many records exist of birds flying 1,000 miles, some have gone much farther. And speeds of more than a mile a minute have been maintained by countless homers on ordinary test flights.

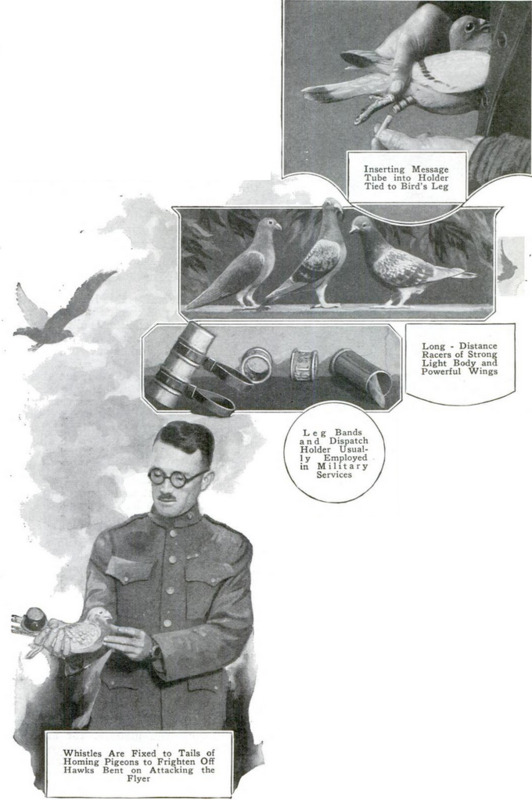

The pigeon division of the United States army was not in existence at the beginning of the war, while the French, German. Belgian and English armies had wonderfully developed branches of this service. The foreign armies had upward of 105,000 birds and 8,000 men each in this service. During the early part of their participation in the war the rapid advance of the Americans found the means of communications very inadequate. Because of the pounding of the heavy artillery, radio was ineffective and telephone service often impossible. It was then that the pigeon came into its own. "The Mocker, greatest of all hero birds, on the morning of Sept. 12, 1918, arrived at his loft from the Beaumont front with his right eye shot out and his head a welter of blood. He carried messages that gave the exact location of advancing enemy batteries. This information enabled the allied artillery to save a whole battalion. When a lone soldier went on reconnoitering duty through the enemy lines, he carried two birds in a small willow basket on his back. Within the basket the birds were placed in small canvas corselets and were suspended by rubber bands so that they would not be injured by the movements of the soldier in walking, falling or running.

Infantrymen were equipped with small silk bags filled with oxygen into which the birds were put when a gas attack came over the lines. At times, the pigeons were with the men in the trenches that were filled with mud and water, and had been without food for days; yet when released, so great was their vitality, they reached their destinations with but few exceptions. Ninety per cent of the messages in France that started out with the birds were delivered.

On the morning of Nov. 5, 1918, "Presi-dent Wilson" arrived at his loft after a flight of twenty kilometers in twenty-one minutes, with the left leg shot off and hanging to his body by one of the tendons. He lost his leg, but delivered the message in jig time. A more lucky bird was "Spike." He delivered fifty-two messages through all kinds of shell fire and in the worst possible kind of flying weather, and was never injured.

About the year 1916 the French introduced the aerial camera. This little instrument weighed scarce two and one-half ounces and was principally made of alumi-num. It was fastened to the breast of the bird with small straps and rubber bands.

Each camera had two lenses, one pointing forward and the other downward. Inside was a small rubber ball pierced by a minute hole. This ball was pumped tight with air. After the bird was released, the air slowly leaked from the container and upon complete collapse released the shut-ter; thus taking the picture.

The bird circled to a height of 100 to 300 feet. It was too small to be hit with bullets and too high for the artillery and gas. The tiny films, when greatly enlarged, gave wonderful intormation. Often the enemy sent up falcons to kill the allied birds, but the French placed small bowllike whistles on the tails of the birds, and when the wind blew against them, a loud whistling noise issued forth to scare away the falcons. As a pastime and sport, the birds are being raised in practically every country in the world by sportsmen who enter them in contests of speed and endurance. Records are carefully kept of all such per-formances, and selective breeding has resulted in producing pigeons that can easily fly 500 miles with an average speed of a mile a minute. Probably the longest distance ever covered during a test by racing homers is a fight from Denver, Colo., to Fall River, Mass., in which two birds flew more than 1,800 miles and arrived at their home loft in good form.

Not only are the birds of great value for military and racing purposes, but they have been entrusted with the exchange of news reports, private communications, and have even been sent with the craft taking part in yacht races to keep those at shore informed as to the progress of the run. Laws have been passed in many countries, making it a serious offense to kill a pigeon, in order to protect the homing variety which at any time may be carrying valuable data.

Like race horses, pigeons which prove of great ability to travel long distances swiftly, are used to stock the flying teams.

Prices paid for them often reach several hundred dollars. One loft of 150 racing homers, recently sold in England, is said to have brought $18,000. Private individuals by the thousand give time and effort to breeding and racing the birds. Societies exist in every state of the union for the purpose of promoting interest in the work, and national contests are annually held to encourage the development of the fleetest kinds. As a rule, the racing homer is so highly bred and schooled that it will refuse to occupy a coop which is not kept in the best condition. Their feed is of selected grains, aged for from one to two years before being given the birds. It is with the help of the pigeons' characteristic fondness for

such feed as hemp seed and rice that trainers are able to teach them distance flying while they are still quite young.

While all pigeons at one time were more or less given to homing, most of them have been bred into show and fancy specimens. The racing homer is the result of careful crossbreeding which has produced a pigeon that has strength, intelligence, and a tall graceful form marked by a light body and powerful wings.

In the days when ancient Rome's legions marched forth to battle, carefully guarded pigeons accompanied them. If the passage of foot messengers was prevented by the enemy, the birds were released with messages to fly over the heads of the opposing armies. Rarely did an imperial prince of those times set out on a long journey without the imperial pigeon cote being included in the train of attendants and equipment.

-

Autore secondario

-

Center Photo Keystone (photo)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1925-04

-

pagine

-

564-569

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Alberto Bordignon