-

Titolo

-

Uncle Sam's Fly-by-Nights

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Uncle Sam's Fly-by-Nights

-

extracted text

-

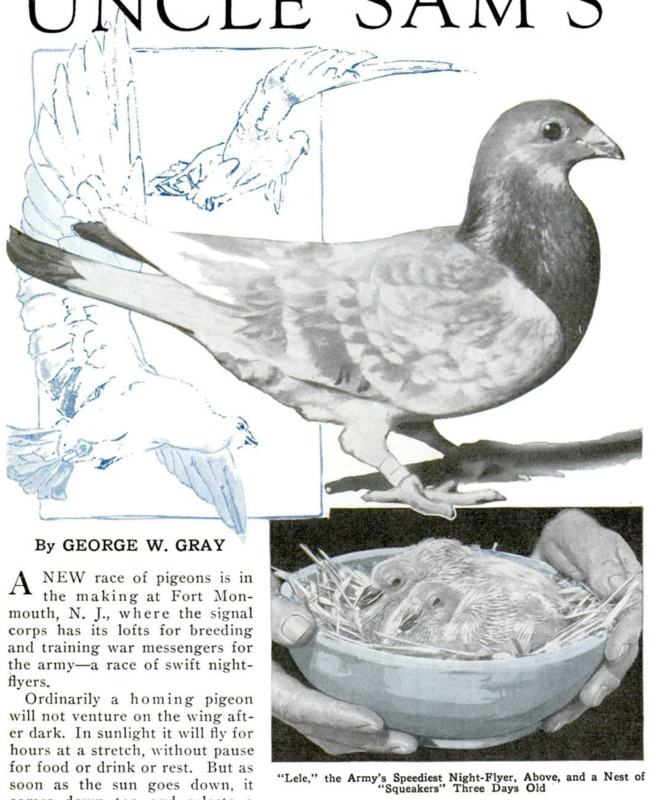

A NEW race of pigeons is in the making at Fort Mon-mouth, N. J., where the signal corps has its lofts for breeding and training war messengers for the army--a race of swift night-flyers. Ordinarily a homing pigeon will not venture on the wing after dark. In sunlight it will fly for hours at a stretch, without pause for food or drink or rest. But as soon as the sun goes down, it comes down too and selects a tree-top roost for the night. With the first peep of dawn it is away again, ready to fly another twelve or fourteen hours if necessary to reach home. If pigeons would fly at night, their value as messengers would be increased manyfold. Not only would night-flyers take less time on long journeys but there would be less risk of their being caught by hawks and other enemies, and of being shot by hunters. Especially in time of emergency would night-flyers be priceless. Of the five pigeons that were released by the Lost Battalion in the Argonne, only one reached headquarters; the others were killed by enemy bullets. One day an official report came from Hawaii to the army pigeon headquarters that electrified the fanciers. It told of four young pigeons that showed a strange fondness for darkness. When released in the late afternoon they flew home the same evening, arriving in the dark. Thomas Ross, chief pigeon expert for the army, checked back, and found the parents of the four birds at Fort Mon-mouth. He selected other youngsters of the same strain, and chose also birds of outside strains that had shown a strong sense of direction. When the eggs hatched, he picked the twelve likeliest "squeakers" as candidates for his night-flying squad. He separated them from the hundreds of others and settled them in a special loft. "All day long the birds were kept inside their loft," said Ross. "A little reflected sunlight was all they ever saw. After sundown, I'd let them out for exercise, and they'd flutter around and try their wings.

Every week I'd make this daily exercise period a little later in the twilight, until finally they were working wholly in the dark. "Then, one evening, I took them out, carried them 100 yards away and released them. My helper stayed in the loft and rattled the food can, and the hungry birds hurried home for supper. The distance was gradually increased until today they are flying seven miles in the dark. They do not do so well in moonlight. A night-flyer wants an honest-to-goodness night to bring out his best powers." The fastest time made by the Fort Monmouth night-flyers is seven miles in ten minutes. Mr. Ross expects ,to raise this speed to a mile a minute. One of the Hawaiian night-flyers has flown eighteen miles at a speed of 1,659 yards a minute, or 101 yards short of the present goal. This speed is not up to the velocities that have been attained by day flyers. An American pigeon has flown 300 miles at the rate of 2,100 yards a minute, which is better than seventy-one miles an hour. "But speed is not the main essential," said Mr. Ross. "Speed depends on so

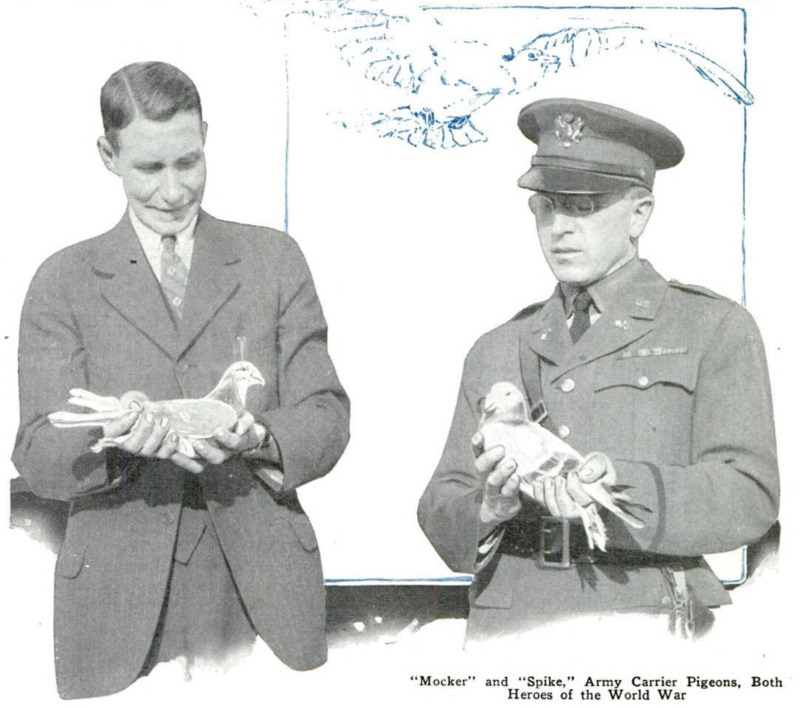

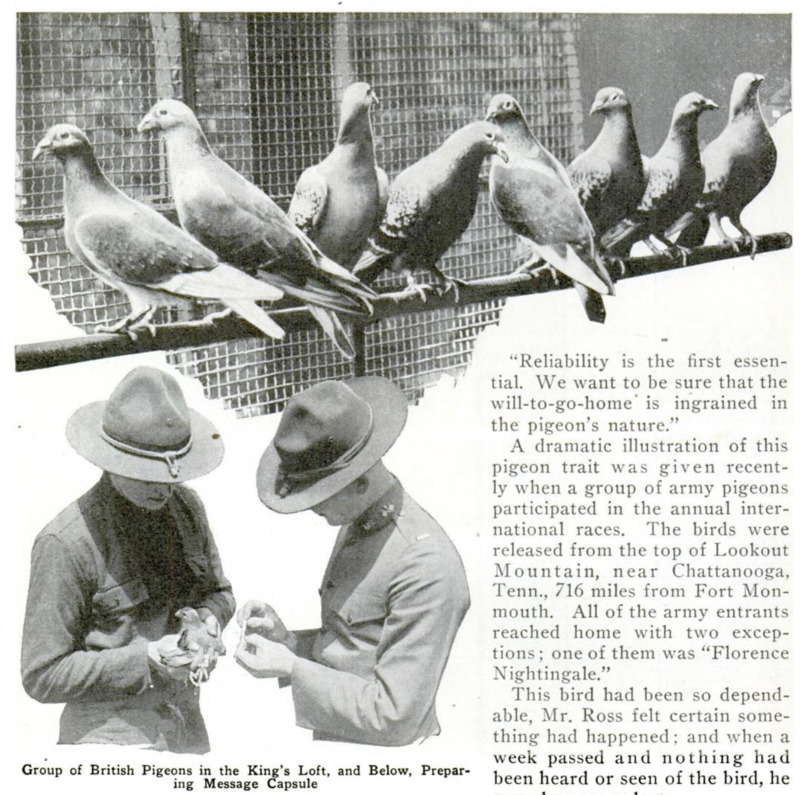

many outside factors- on the weather, direction of the wind, fogginess. A pigeon won't fly in a fog, and for some unknown reason an east wind slows it down. "Reliability is the first essential. We want to be sure that the will-to-go-home is ingrained in the pigeon's nature." A dramatic illustration of this pigeon trait was given recently when a group of army pigeons participated in the annual international races. The birds were released from the top of Lookout Mountain, near Chattanooga, Tenn., 716 miles from Fort Mon-mouth. All of the army entrants reached home with two exceptions; one of them was "Florence Nightingale." This bird had been so depend-able, Mr. Ross felt certain something had happened; and when a week passed and nothing had been heard or seen of the bird, he gave her up as lost. One noon, twenty-four days after the race, "Florence Nightingale was found hopping along the ground in front of her loft. Her right wing dragged helplessly.

The bone had been shattered by a bullet. Some hunter, seeing a flying bird, had shot her. Another promising hen pigeon, "Molly Pitcher," was among the missing. Twenty-five days later a message came from Camp Dix. An officer there had seen a pigeon drop out of the sky and flutter to the ground. He found it was wounded, and its leg tag identified it as one of the Fort Monmouth stock. Mr. Ross recognized at once his missing "Molly Pitcher." She too had been the victim of a shotgun. "But in spite of pain and hunger, she had kept on the homeward way," said Mr. Ross, proudly. "Camp Dix is between Chattanooga and Fort Monmouth, and when she reached it, she must have been near exhaustion. She saw below her an army camp, a place that was not Fort Monmouth but akin to it. So she landed and allowed herself to be caught. I count her one of the smartest birds in the army." It is this kind of reliability plus intelligence that Mr. Ross hopes to develop in the new race of night-flyers. He wants the birds to be so dependable that, if ever again there is a Lost Battalion, it can release a pigeon under cover of night and feel confident that it will fly immediately to headquarters.

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1931-12

-

pagine

-

954-957

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Alberto Bordignon