-

Titolo

-

Robot Warships

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Robot Warships

-

extracted text

-

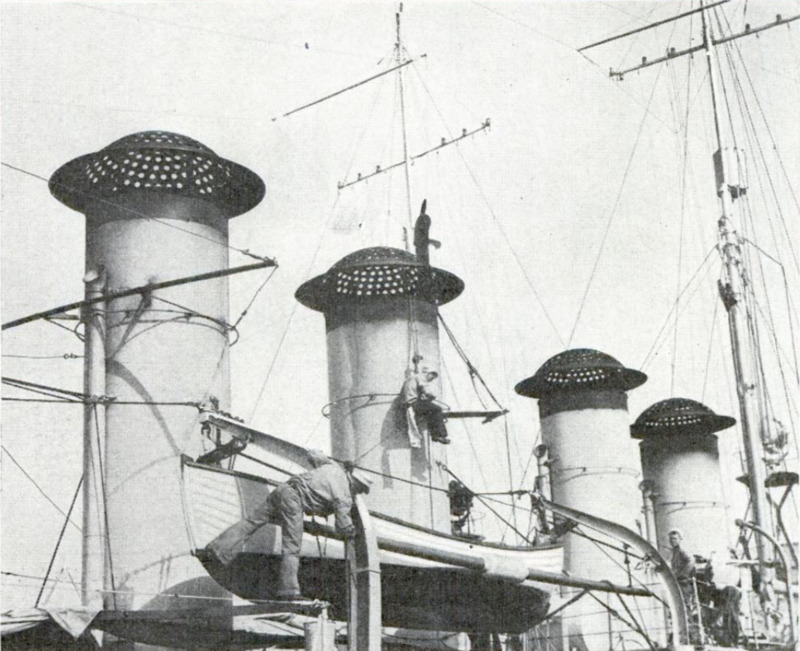

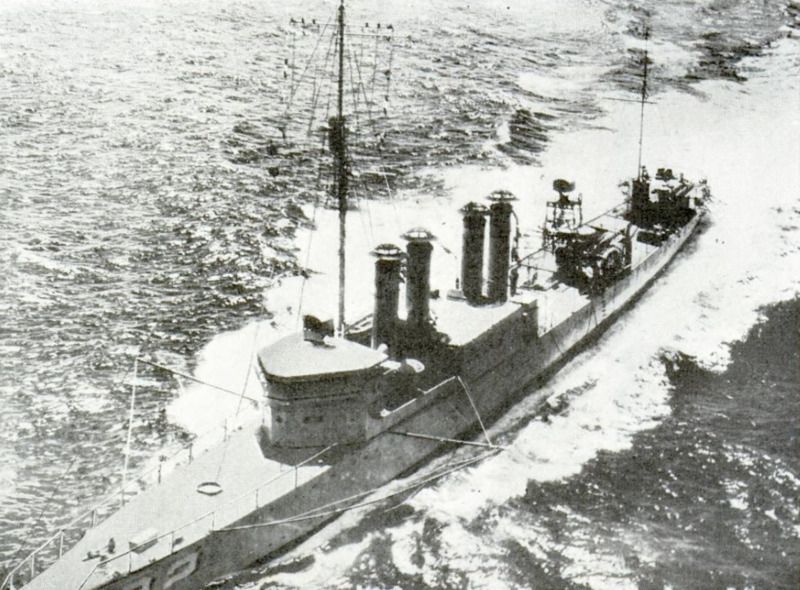

OUT through the Golden Gate steamed a lean grey destroyer, different in no respect to the casual eye from any of the sea greyhounds frequently to be seen traversing that waterway. But on that entire craft there was no human being. Its engines turned, speeded up, slowed down, without the touch of a hand. As deserted as any derelict, it nevertheless performed its every function as though manned by a full crew.

Half a mile behind it was another destroyer, fully manned. On its bridge was a metal box about the size of a portable radio. Standing beside this, his hand on a small keyboard, was Lieut. Com. Boyd R. Alexander, commandant of the navy's mobile target division No. 1, and inventor of The world's first robot fighting ship. From time to time Commander Alexander's fingers depressed a series of the white keys-there are only nine of. them altogether-in such combinations as a typist might use in writing a couple of short words. Each time the ship ahead changed its course or its speed, or both. Once it tooted twice at a fishing boat. The principal use of the robot type of ship in peace time is a mobile target for bombing planes. The robot boat, "Boggs," for instance, is taken out to sea and sent out far ahead of the control ship. Bombing planes fly over it and try to drop non-explosive missiles aboard it, while the "Boggs," controlled from afar, makes the same maneuvers to escape being hit that an enemy ship would make in war time. But it is as offensive and defensive units of the navy's active forces that the most important and startling possibilities of the robots are to be realized.

Out in those blue wastes where there is still some privacy in a crowded world, the robots have been tested in mimic naval engagements of many different varieties. The experiments have revealed some of the almost incredible things that may be expected of the robots in time of war-some of them only, for there is little doubt that many others, perhaps even more startling, remain unguessed at. The robots have been maneuvered against actual fleets; their guns have been fired upon moving targets. An enemy fleet is sighted steaming toward our coast. Out goes a robot ship with a control ship behind it, and on the deck of the latter a hydroplane. Long before the control ship has come within sight of the enemy it heaves to, and the plane goes forward scouting. It sends back a radio message giving the position of the fleet, and the robot is sent forward, far out of sight. The airplane reports its position, together with that of the enemy. Now the robot is reported within firing distance, and a new set of positions is given, from which the gunnery officers on the control ship calculate the exact range and deflection for the robot's forward guns. A combination of keys is touched, and far over the horizon the robot guns swing uncannily into position. Another key, and a shell screams into the enemy's midst. As everyone knows, a radio system can be rendered totally ineffective by the simple device of getting on its wave length and filling the channel with irrelevancies. But first you must catch your rabbit. What are the wave lengths in the present case?

So far no instrument has been devised that will detect a radio signal without patient tuning unless it is already set for it. And to tune onto a short wave is not a matter of locating a broad band, as with the low frequencies, but a hair line.

This could be done in time, of course, if the signals were being repeated continuously on that same hair line. But in less than a second the four or five signals necessary to set any part of the robot's mechanism in operation zip through the air and are gone. It is in a small part of that second that the enemy must tune onto the fine ether channel occupied by any one of them. That instant gone, it is too late until the next signal- -when again opportunity will be so small that it would rattle around in the breadth of a watch tick.

But suppose that by a chance too remote for practical consideration the enemy succeeded in identifying those frequencies, there would still be the task of setting up and maintaining precisely similar ones.

Granting again the virtually inconceiva-ble, that before suffering irreparable damage from the robot's guns the enemy could identify and reproduce those sparse and elusive signals, they would find they had had their labor in vain. For the control ship would simply shift onto an alternative set of frequencies.

Another way in which the robot can be used to great effect in war time is as a mobile mine to guard our harbors. The present mine system has one defect-it cannot work till the enemy gets close enough to bombard the port and its defenses without risking the mines at all. But a robot ship loaded with nitro-glycerine is another matter. Long before the enemy can get within effective bombarding range he finds the mines leaping at him out of the long blue swells, and unless he is foolish enough to try to fight them off, pursuing him far out to sea. There is only one answer to robots, and that is robots. Regardless of the fact that an enemy would probably never get a chance to copy one of ours- for it would be blown up as he stepped on board of it-ships based on the same principle will, of necessity, be devised by other nations. It may be a long time before they will hit upon a mechanism that will operate as effectively, but they will assuredly develop some type of ship subject to remote control. And then robot fleets will meet and fight it out in the open sea.

What kind of battles these will be, no one can now speculate. They will be battles in which no lives can be lost, and which the only conscious participants will watch through spy-glasses. The possibilities of maneuvering when neither leader need hesitate, for humanity's sake, to sacrifice a "piece," and when the pieces can be played upon as deftly as the stops of a flute, cannot yet be realized. One thing is probable, however the robots would make naval warfare more humane.

-

Autore secondario

-

Harold J. Fitzgerald (writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1934-07

-

pagine

-

72-75

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Alberto Bordignon