-

Titolo

-

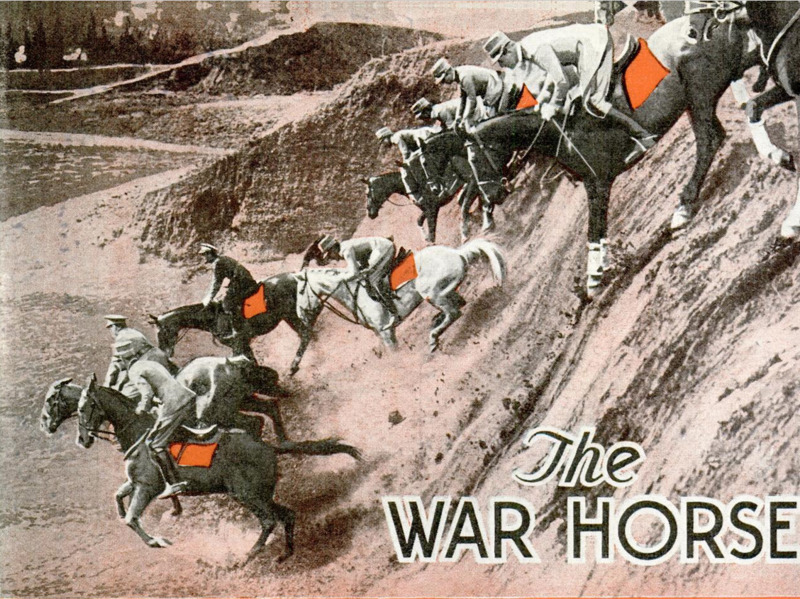

The War Horse at School

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

The War Horse at School

-

extracted text

-

HAS the day of the horse in war gone never to return? In these days of machine guns, armored tanks, bombing planes, poison gas and chemical war-fare, there is a large school of military strategists who say that the horse has no place in the modern armies, and will very soon be relegated to museums beside bows and arrows, rusty armor, spears, lances and battle-axes.

"Oh no!" retorts another influential school of military scientists. "Even in the last war, with thousands of internal combustion engines and motor vehicles available, the horse had his place. There are, all over the world, plenty of wooded and hilly countries where mechanical transport is practically impossible even with caterpillar tracks-and here the horse may be very effectively used to cooperate with armored fighting vehicles and infantry." France, which not long ago erected a striking war memorial to the 1,140,000 French horses which fell on the field in the great war, does not believe the war horse has had his day. Today, at leafy Saumur, on the river Loire, in western France, the French government maintains a remarkable cavalry training school which was founded in the days of Napoleon Bonaparte. Here, under the control of the French war department, 400 cavalry students, carefully chosen from all French mounted regiments, and also coming from the military academy for cadets, at Saint Cyr, are trained in riding and equestrian display. The Saumur school has its own corps of signalers, telegraphers and wireless operators, and a special establishment for training veterinary assistants. A French soldier, in the mounted army, who wants to qualify for the higher pay and more responsible position of cavalry corporal must have first served four months in the field. But, if he wishes to qualify for a commission, he must obtain entrance to the cavalry school at Saumur. The young horses are early accustomed to the sight of the glittering sword, or cuirass, the bridle, headdress and sky-blue uniform. No matter whether he is standing, walking, or on the march, the horse must be taught not to fear gunfire. He has to be present at all rifle practices and, step by step, is made used to the sound of the firing of field guns and large ordnance. The aspirant has to get into the mind of the horse, by studying him at all times.

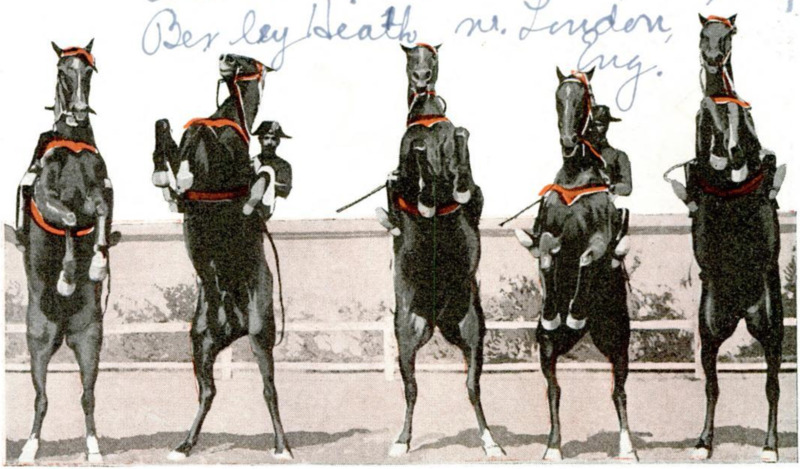

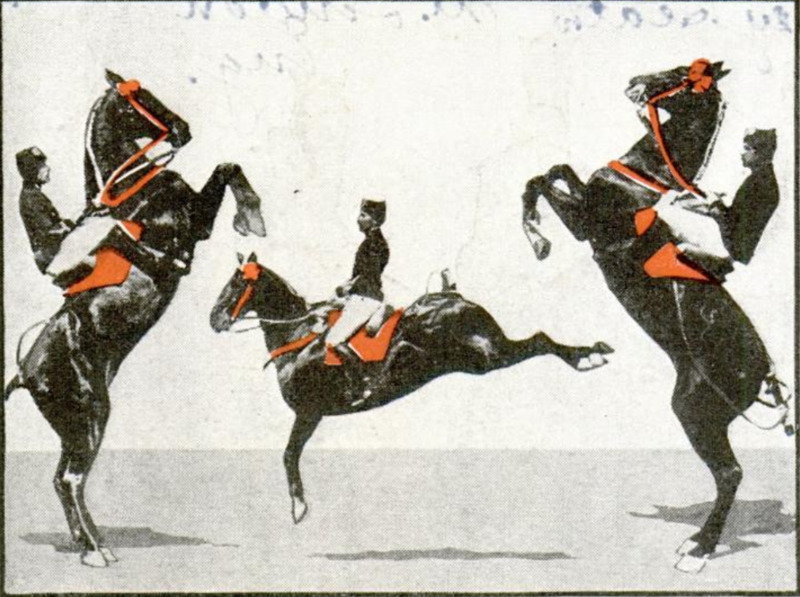

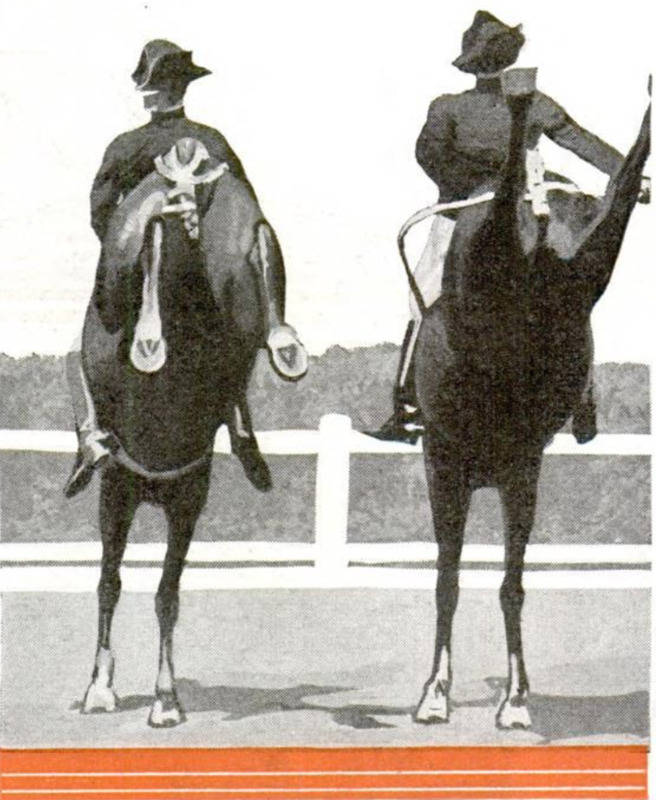

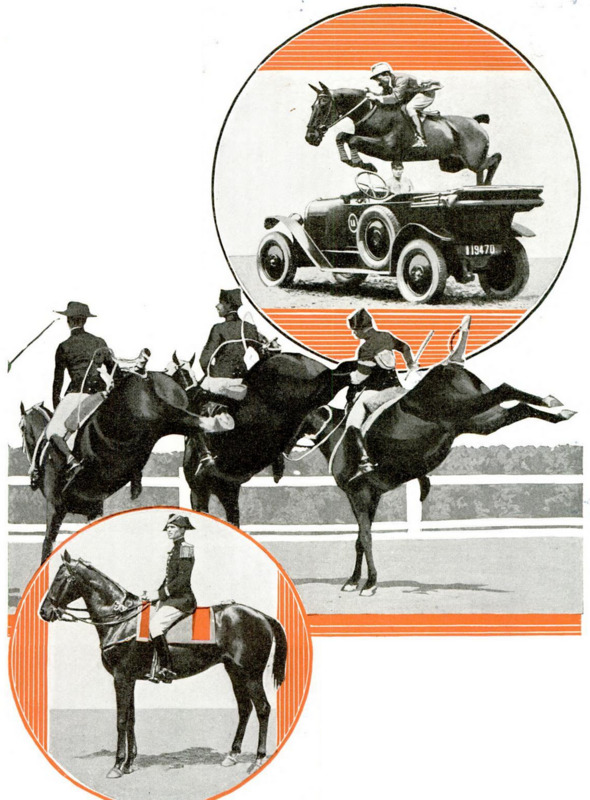

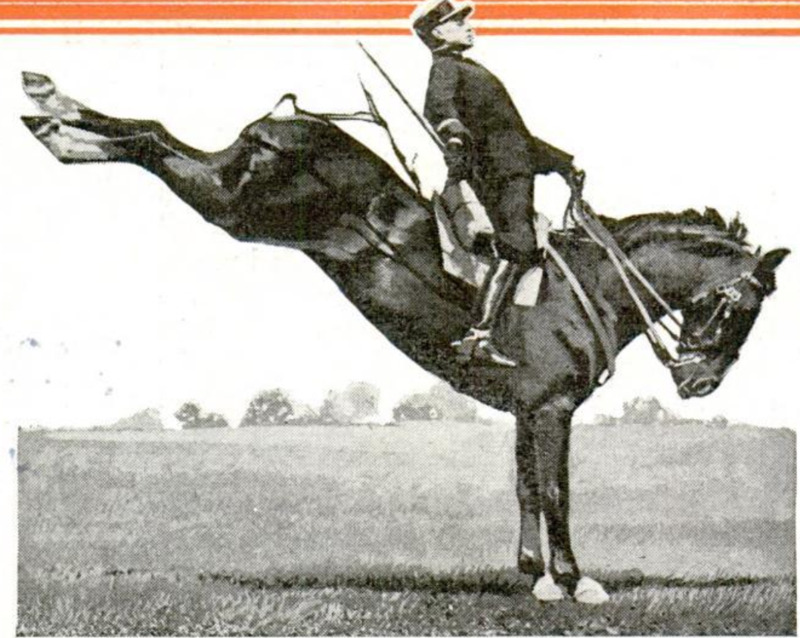

The horse has a memory, and the man must be careful not to teach the horse wrong lessons. If he does, it will be probably next to impossible to unlearn the horse. Some horses are dull, some quick in apprehension. The latter quality is usually the mark of the thoroughbred. But whether the horse be slow or smart in his reactions, blows will not bring him to reason, or make him quicker. They will make him either vicious and irritable, or destroy his spirit and make him timid and, obviously, unfit for military purposes. Remarkable displays of trick riding are part of the course. The riders, generally, use no stirrups, but rely solely on pressure of knees and light touch of the supple hands on the reins. A kind of buck-jump-ing called the "croupade," in which the horse leaps as he tucks his hind feet under him, starts off the annual displays, called him, starousels." These are the direct descendants of the knightly jousts and tournaments held in medieval France. The horses are made to dance to band music or the strains of lively military marches. And these equine dances are done singly, or in companies of seven or a dozen young and graceful chargers. Another evolution, called the "courbette," shows the horse rearing almost upright on his hind legs, while the rider, without stirrups, maintains exactly the same position, in relation to the animal, as he would were the horse standing still in the normal position. Then the horses perform in companies. Two horses with riders, stand upright in the courbette, while between them a third horse, with rider on his back, performs the croupade, leaping by rearing with his hind legs tucked under, and head toward the ground. Another performance shows half a dozen horses standing upright on their hind legs, while, with riders mounted, their front legs and hoofs are curved like the paws of dogs standing up begging. The same horses and riders reverse and perform a similar trick, but with their sterns to the spectators, and standing on their hind legs. But the most interesting and striking performance of the carrousel takes place in the barrack square. when about twenty soldiers, in uni-form, and sitting or standing at a table covered with a white cloth, and set with glasses and bottles of wine or vermuth, toast horse and rider as the skilful animal jumps over them, without so much as flicking cloth, glasses or men. Similarly, a motor car is halted, and the horse, with rider in the saddle, bounds clear over the car.

-

Autore secondario

-

Keystone View Co. (photo)

-

Zenipictures (photo)

-

Saumur School of Military Riding (photo)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1934-09

-

pagine

-

402-405

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Alberto Bordignon