-

Titolo

-

Military Jeeps in the Post-War Period

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

1001 Postwar Jobs for the Jeep

-

extracted text

-

OUR little wonder warrior, the American jeep,** which has won unbounded admiration by its performance on fighting fronts and behind them in every quarter of the globe, is not going to have any difficulty in finding employment after the war.

This was made clear by the flood of ideas submitted in our contest (announced *P.S.M.*, Aug. ’43, p. 101), for the best suggestions on peacetime jobs for the sturdy, overpowered little machine. And, judging from the letters submitted by contestants, the jeep’s reward for its part in winning the war is likely to be, for the most part, a lifetime of hard work down on the farm.

Out of almost 1,200 persons who entered the contest, more than 400, including the winner of the first prize, thought the proper postwar place for the jeep was the farm, where its chores would take in about everything now performed by man, beast, and machine, from plowing to harvesting—and then on to marketing.

Letters came from every section of this country, as well as from Alaska, Canada, Cuba, and South America. Many came from men in the armed services, who spoke of the jeep not only with pride but with affection. Scores of contestants cleverly illustrated their suggestions. A few turned to verse to express their ideas, and one ingenious entrant even worked out an acrostic to boost the jeep’s potentialities. So numerous and so meritorious were the ideas submitted that *POPULAR SCIENCE* increased the number of prizes from eight to 11 and included 11 honorable mentions.

Jobs were found for the jeep not only in the fields but in the forest and the factory, on city streets and on the cattle range, in railroad and highway construction camps, at airports, on golf courses and race tracks, on college campuses, and on backwoods roads leading to favorite fishing waters.

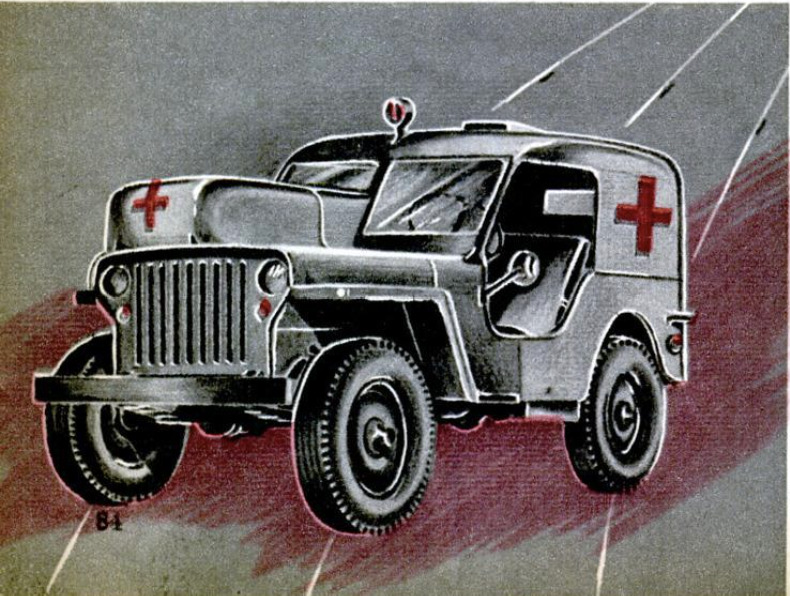

It was assigned to postmen and doctors in rural districts, to road surveyors and inspectors, to electric-power workers, to telephone and telegraph wire stringers, and to a wide variety of construction, maintenance, and repair jobs. Some suggested it be turned into an ambulance, for service not only in poorly developed sections of this country, but also in China, India, and Africa, where it would help to carry on the work of American humanitarianism.

Many saw the peacetime jeep as an aid in the protection of life and property. These assigned it to police duty—local, state, and F.B.I.—and fire fighting, particularly in the forests. More than 200 suggested converting the machine to commercial uses, mostly as a light delivery truck, and into a pleasure car.

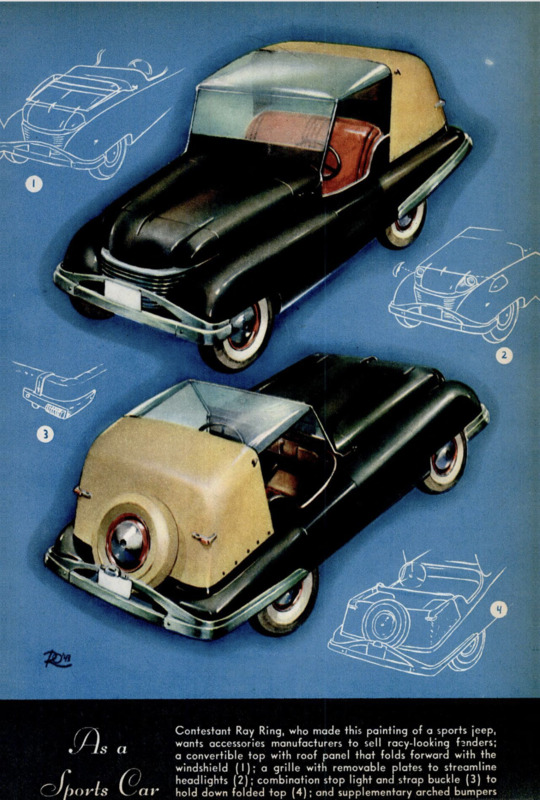

Some of the conversion ideas called for considerable alterations. An example of the imagination used in transforming a jeep into a sports car, disguised by streamlining and radiant in paint and plastics, is shown in an airbrush painting in full color submitted by Ray Ring, of Framingham, Mass., and reproduced on page 85.

Incidentally, the idea of prettying up the jeep to serve as a pleasure car drew cries of pain from servicemen. While most of them expressed hopes of owning a jeep after the war, many of them simply for the pleasure of driving it around, the servicemen wanted it to retain its present rugged homeliness. Lt. W. L. Hoffman, of Camp Forrest, Tenn., who was awarded a prize, voiced this opinion:

“In the service we all know and love the jeep (the one-quarter-ton truck to us). We’ve driven it and nursed it, cussed it and blessed it. We know that it’s the best car in the world—for the job it was meant to do; but to make a pleasure car out of it—never! That would be like dressing one of our tough old ‘top-kicks’ in diapers. The jeep was meant to do a man’s job in rough country—not to take ‘old women’ to tea parties.”

“But,” he continued, “there are many jobs for jeeps in peacetime—jobs that are commensurate with its abilities. On the farm, for instance, they’ll do anything a horse will do, except whinny—and you don’t have to feed them when they’re not working.”

Lieutenant Hoffman’s omnibus reference to the jeep’s farm-work potentialities was amplified by the first-prize winner, R. W. Radelet, of Vancouver, B. C., who emphasized the value of the jeep to the small farm operator who can afford only a single machine. In such hands, he said, the jeep could be used in the orchard for spraying and picking. In the fields it could be used as a tractor with a gang plow, a mower, and a rake. It could also be used as a truck and a trailer car to haul produce and stock. It could be employed as a stationary power plant, and it could carry workers to and from the farm.

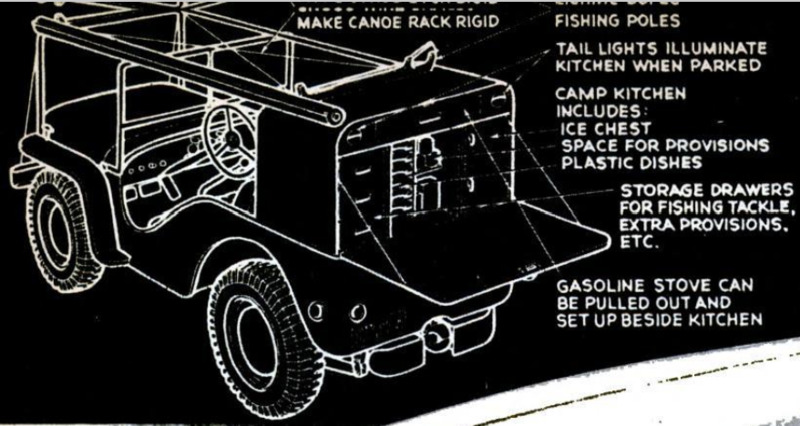

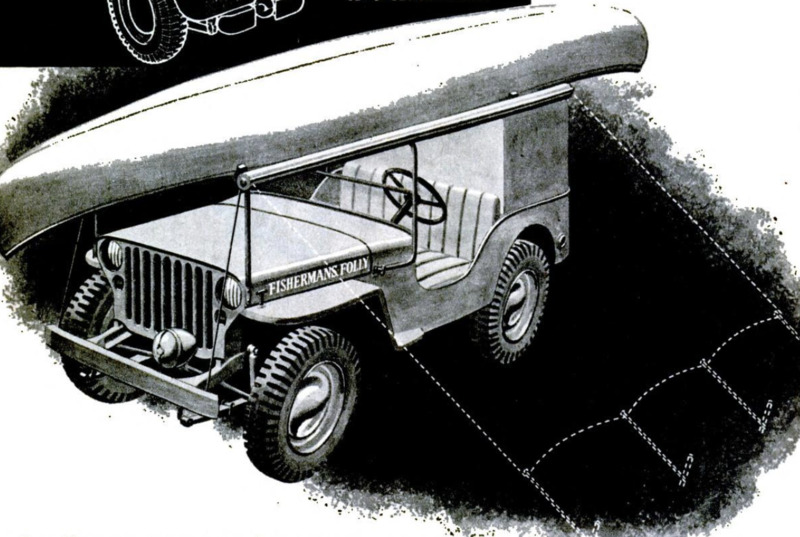

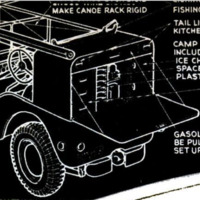

A soldier with his mind on the pleasures of peace won second prize with an idea to adapt the jeep to a “fisherman’s folly.” A rack on top could carry a canoe, and the back seat could be converted into a camp kitchen, with ice chest, plastic dishes, storage drawers for fishing tackle and provisions, and a gasoline stove. Rollers at the sides would enable the lowering of canvas to make the jeep a shelter. The soldier, Pvt. Ronald E. Doan, of Camp Sibert, Ala., suggested that all the attachments “could be sold as a unit, to be installed by a local mechanic.”

“The ‘folly’s’ four-wheel drive,” he wrote, “would pull it farther into the backwoods and nearer to unfished streams than any pleasure car would dare to venture. Upon arriving at your selected spot, pull down the roller tent, open up the kitchen, and there’s your camp—deluxe and Dad’s delight.”

The winner of the third prize, S. M. Farmer, of Chestertown, N. Y., envisioned a dozen uses for the peacetime jeep, the first of which was to transport men and equipment to forest fires in remote areas, where its ability to travel over logging and tote roads gives it a big edge over regular cars and trucks. This same ability, he said, would make the jeep useful to logging companies, in hauling supplies by trailer. He also suggested that the jeep be used to carry doctors, police, and border patrols over roads choked with snow or mud, that it be used on farms as a tractor and a pick-up, and that it supplement riding horses at summer hotels, which could rent jeeps to guests to tour the surrounding country.

Among ideas for converting the jeep into a forest-fire truck was the prize-winning entry of Ernest Prete, of Staten Island, N. Y. He proposed that the jeeps be covered with a thick asbestos shell and equipped with a revolving turret with two nozzles, “which would shoot water the same as the turret guns on an airplane shoot bullets.” A sprinkling device attached below the front of the radiator would spray ground fire. Water for the apparatus, when not available from streams or lakes, would be drawn from a tank car towed by the transformed jeep.

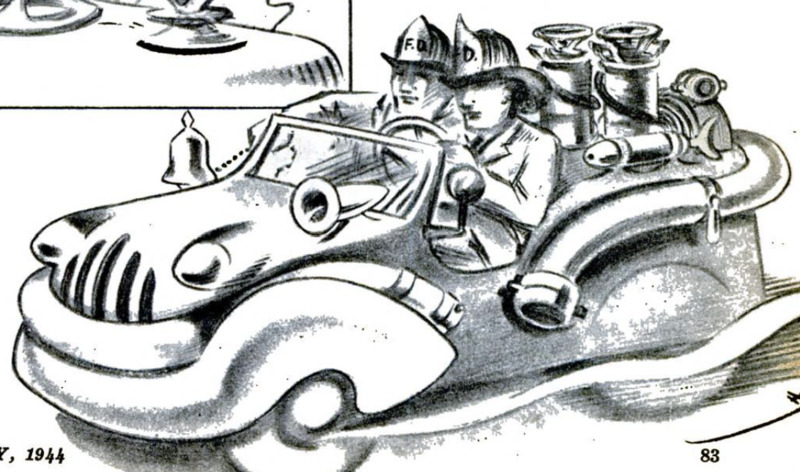

Joseph Krucher, of New York City, also won a prize for his suggestion that the jeep be turned into a hose cart for city and rural fire departments. With its speed and maneuverability, it could race through traffic and have the lines attached to hydrants and ready for action by the time the heavy pumpers arrive. He also suggested that fire departments use the machine as a searchlight unit.

One of the most interesting letters was submitted by Tommy Bransford, 16 years old, of Lonoke, Ark. His letter, which contained an even dozen ideas, was awarded a prize. Farmers, rural doctors, mailmen, forest rangers, sportsmen, service-station operators, and cowboys “riding the fence”—to inspect it for breaks—were among his potential users of the peacetime jeep.

In his suggestion that the jeep would be ideal for hunting and fishing trips, Tommy considerately thought of the women folks. With a converted jeep, he explained, a man “could go without worrying about taking the ‘good’ car away from his wife, who hates to have old fishing smells in it for months after one of his trips.”

A considerable number of contestants brought up the point of how the Government would dispose of the jeeps. Some took it for granted that they would be sold in huge lots to manufacturers and dealers. But this disposal method was vigorously opposed by others, who saw in it a threat to the new-car market after the war. One of these, Pfc. Robert W. Huzzard, Army Air Forces, Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio, won a prize by suggesting that the jeeps be converted into ambulances and given to the American Red Cross for work in the Orient and Africa. The drawing which accompanied his entry is reproduced below.

Another opponent of putting jeeps on the open market was Edwin T. Brown, of Wilkinsburg, Pa., who urged that we give the jeeps to our Allies or “bury them where they are” when peace is attained. He advised manufacturers to scrap their dies after the war and go on with the building of the automobiles of the future. Consigning peacetime jeeps to the category of toys, he declared: “We have to get on with the building of helicopters.”

Perhaps a partial answer to this argument was contained in the suggestions that peacetime jeeps be used to haul the great planes of the future onto and off the landing fields, and to shuttle material and men around aircraft and automobile factories. Other contestants believed the jeeps should be sold or rented by the Government directly to the persons who would use them. Pfc. Ralph R. Brown, in a V-mail from overseas, suggested that the Government establish depots at discharge points and sell or auction the jeeps to men leaving the service. Another serviceman proposed that a soldier be given his choice between a jeep and a bonus.

In a letter from Treasure Island, Calif., a U. S. Marine stated his wish simply:

“Like many another serviceman, I’d like to own one after the war—but no fancy paint, bright aluminum, white side walls, or brassy horn for me. You can put me in an order for one just as it is.”

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1944-02

-

pagine

-

80-85

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Lorenzo Chinellato

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)